Sarah stares at her screen, cursor blinking in the empty text box. Question 47 of 52:

“Please demonstrate how people with lived experience are meaningfully involved in your decision-making processes. Include evidence of their influence on organisational strategy in the last 18 months.”

She’s been working on this application for three weeks. The deadline is tonight. This is her fourth application this month, each one requiring the same information presented in slightly different formats.

She scrolls back up to review her earlier answers. Question 12 had asked for detailed documentation of her trustees’ potential conflicts of interest, including any business relationships that might influence their charitable giving. Question 23 wanted a full ethical audit of how her family’s wealth was originally accumulated, with particular attention to historical labour practices and environmental impact. Question 31 demanded proof that her investment portfolio was fully aligned with the values of every organisation she hopes to support.

She takes a breath and starts typing again, explaining for the dozenth time why her foundation’s governance structure qualifies her to give money away responsibly. The wealth is there – sitting in accounts, waiting to create change – but explaining why she deserves to distribute it feels increasingly divorced from actually doing any good.

Sarah submits at 11:57 PM. In six months, she’ll hear back. Maybe.

An Alternative Reality

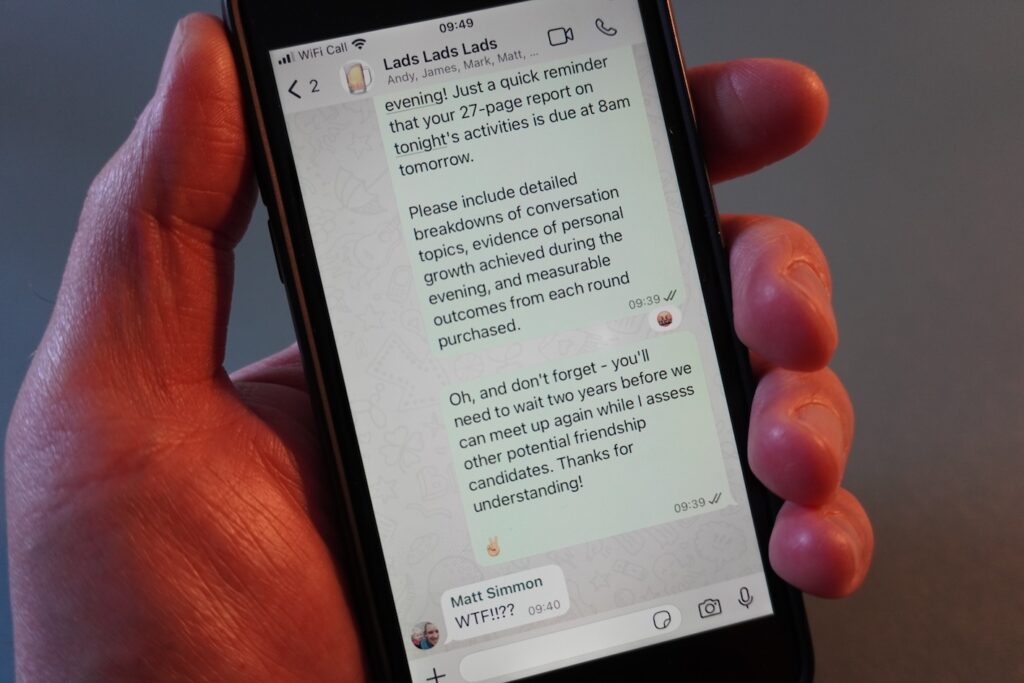

Imagine if impact was the scarce resource. Sarah and hundreds of other philanthropists like her are begging charities to accept their money. Overwhelmed with applications from wealthy individuals desperate to give away their fortunes, charities have developed elaborate systems to sift the wheat from the chaff. They’ve designed the “impact application” – putting funders through the same gruelling processes they currently endure.

The Impact Application would demand:

- How are you governed? Show us your board minutes from the last two years

- Do your trustees have conflicts of interest? Provide full financial disclosures

- How was your endowment originally produced? Demonstrate that your wealth creation followed strict DEI guidelines throughout your entire business history

- How is your money invested now? Prove your portfolio aligns with every cause you claim to support

- What’s your gender pay gap? Not just in your foundation, but across all your business interests

- How do you involve people with lived experience of wealth management in your decision-making? (Though admittedly, most funders might score well here!)

And the terms would be equally demanding:

- You can’t give us half of what we ask for – it’s either 100% or don’t waste our time

- Since we’re experts at delivering charitable objectives, we’ll determine what the money will most effectively pay for. You understand wealth management. Great. We understand impact delivery. Let us do our job, the same way you wouldn’t expect us to tell you how to manage your investment portfolio

- No funding without a three-year commitment – we can’t build sustainable change with one-year grants any more than you could build a business with one-year contracts

From Rule-Breakers to Rule-Makers

Here’s what’s fascinating: many of today’s major philanthropists made their fortunes by breaking rules, taking massive risks, and ignoring conventional wisdom. They succeeded as entrepreneurs precisely because they didn’t ask permission, didn’t follow templates, and certainly didn’t spend months filling out applications explaining why their ideas deserved to exist.

Yet when they turned their hand to philanthropy, they adopted the opposite principles. They created a system that demands the very people trying to solve society’s most intractable problems – the social entrepreneurs of our time – behave like risk-averse bureaucrats. We’ve created a system where Steve Jobs would never have been funded to build Apple, but we expect the people trying to fix homelessness, climate change, and inequality to submit 40-page applications explaining exactly how they’ll spend every penny.

Business leaders regularly complain about the slow, bureaucratic, and cumbersome public sector. But here’s the uncomfortable truth: modern philanthropy learned these practices from government. The grant application, the evaluation framework, the reporting requirements – none of these were philanthropic innovations. They were tools of administrative governance that private foundations embraced because they offered control disguised as accountability.

And this matters more than ever. At a time when even the state can’t be trusted to act in the public interest – hello America! – philanthropy has always been independent, able to act outside party politics and business imperatives. Yet we’ve created systems that mirror the very bureaucracies we claim to transcend: prove you’re worthy, don’t risk our reputation by association, show us your five-year strategic plan for work that’s never been done before, measure outcomes that may not emerge for decades.

What Philanthropists Could Learn From Angel Investors

Angel investors understand something fundamental: breakthrough innovations come from backing people with vision, not funding detailed business plans. They know that the most transformative companies pivot from their original idea. They expect most investments to fail because they’re betting on the few that will change everything.

Successful investors do their due diligence on the entrepreneur, not just the spreadsheet. They ask: Does this person have the drive, intelligence, and resilience to navigate the unknown? Do they understand the problem deeply? Are they obsessed with solving it?

Compare this to grant-making, where we focus on detailed project plans for work that by definition has never been done before. We demand certainty in contexts of radical uncertainty. We require compliance with processes that would kill innovation in any other sector.

The Civil Society We’re Creating

This matters because it fundamentally shapes what kind of civil society we get. Are we funding organisations that quietly sweep up the failures of state and private sector? Or are we empowering movements that howl with rage against broken systems and have the resources to actually smash and rebuild them?

The current paradigm creates what might be called “soft authoritarianism” – a compliance culture that constrains radical thinking through bureaucratic processes rather than outright censorship. When organisations spend vast amounts of time on applications and reporting rather than delivery, when they must pre-define outcomes for undefined problems, when they’re discouraged from advocacy that might seem “political,” we’re not getting the full potential of civil society.

The social entrepreneurs who could be tackling systemic injustice are instead managing grant portfolios. The movements that could be challenging power structures are writing monitoring and evaluation frameworks.

Back to Philanthropy as Radical Gift

Let’s return to the original notion of philanthropy as gift. As freedom. As a vote of faith in people with vision who are never going to create change by playing nicely within the bounds of existing systems.

The word “philanthropy” means love of humanity. Love doesn’t come with 27-page application forms. Love doesn’t require quarterly reports. Love trusts the beloved to know what they need. It backs them through thick and thin, supports them to be their best self, wants to see them grow and flourish. Love isn’t conditional on perfect outcomes – it wants the best, but it doesn’t withdraw when things get difficult. It challenges and pushes for excellence, but it doesn’t undermine or control. It believes in potential even when the path isn’t clear.

This doesn’t mean abandoning all oversight – even angel investors want to see how their money is being used. But there’s a difference between accountability and control, between stewardship and micromanagement.

What This Could Look Like

Imagine funders who operated more like entrepreneur-investors than bureaucrat-gatekeepers:

- They’d back people, not projects

- They’d expect pivots and adaptation, not rigid adherence to original plans

- They’d provide multi-year core funding, not project-specific grants

- They’d measure success over decades, not quarters

- They’d celebrate bold failures that generated learning, not just safe successes

- They’d see their role as removing barriers, not creating them

This isn’t anti-accountability – it’s pro-effectiveness. It’s recognising that the people closest to social problems are often best placed to solve them, if we give them the freedom and resources to do so.

The entrepreneurs who built the empires that endowed many of today’s largest foundations weren’t wallflowers who quietly accepted the status quo. They were risk-takers who did things differently.

The OGARTA Vision

This thinking drives Raiser’s OGARTA approach: One Grant Application to Rule Them All. Instead of charities spending months crafting bespoke applications for each funder’s specific requirements, they describe their impact on their own terms, in their own language, focused on their own vision of change. Funders can then get in line to support work they believe in.

And for anyone familiar with the Tolkien reference, you know the One Ring’s ultimate destiny: it had to be destroyed so people could be free. Something with the power to control others should never be allowed to exist. That’s exactly what the modern grant application paradigm does – it concentrates power in the hands of those with money rather than those with expertise in creating change.

The current system needs to be thrown into Mount Doom where it belongs.

It’s time for philanthropy to remember its entrepreneurial roots and start funding like it believes change is actually possible.