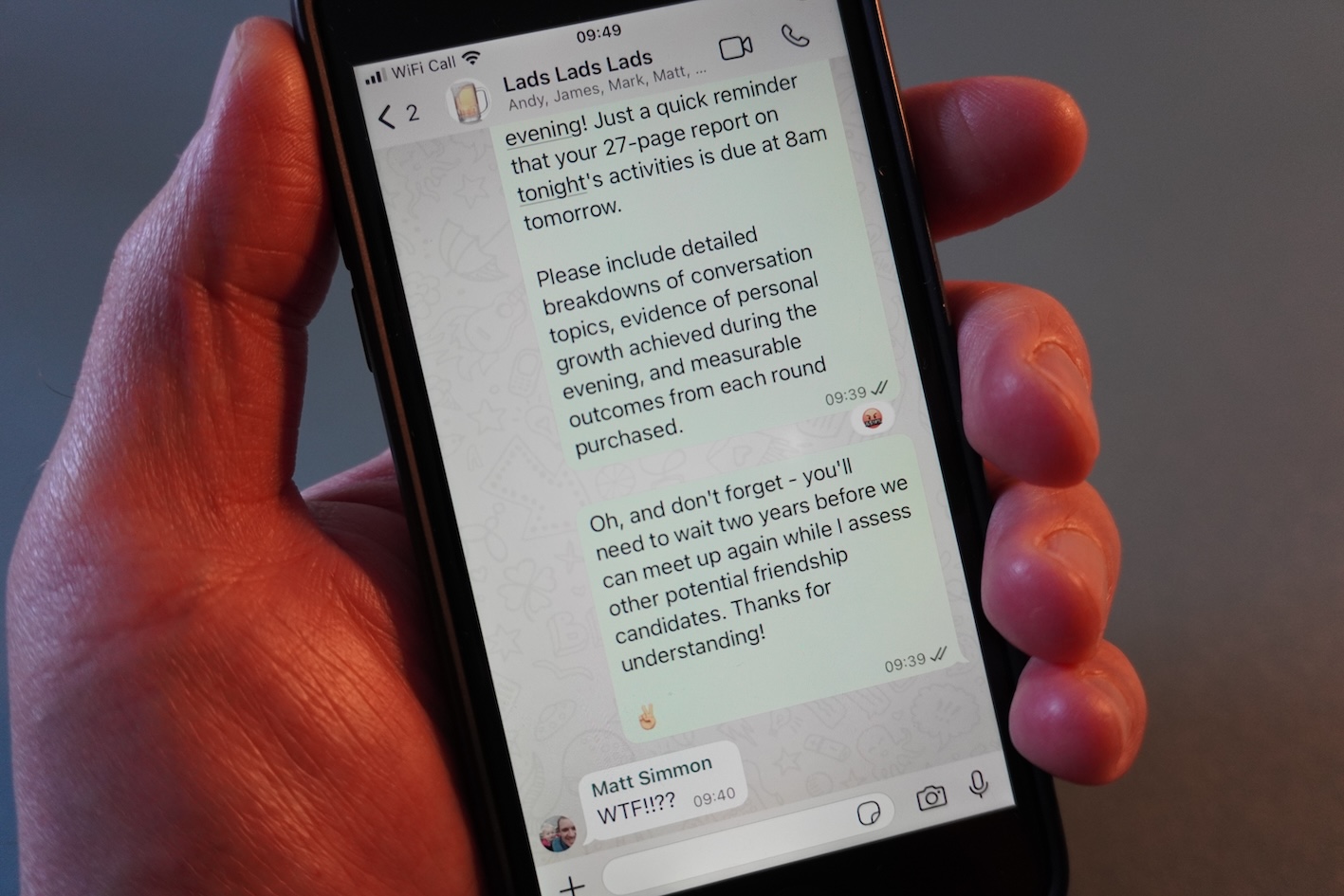

The group chat pings at 11:47 PM: “Hi guys, great to hang out this evening! Just a quick reminder that your 27-page report on tonight’s activities is due at 8am tomorrow. Please include detailed breakdowns of conversation topics, evidence of personal growth achieved during the evening, and measurable outcomes from each round purchased.”

“Oh, and don’t forget – you’ll need to wait two years before we can meet up again while I assess other potential friendship candidates. Thanks for understanding! ✌️” – Funda

Matt stares at his phone. He’d just wanted a pint and a chat about football. Now he’s apparently in some sort of performance review process that makes his annual appraisal at work look casual. “Funda? More like Fun Police,” he mutters.

This sounds ridiculous because it is. But this is exactly how modern grant funding relationships work.

The friendship test

Real friendships don’t operate like this. You don’t think of someone as a genuine friend if you just have a couple of selfies together and text once a year on their birthday. You wouldn’t start a friendship by saying “I’ll be your mate for exactly twelve months, then we’re done for the next five years while I make some other friends.”

Friends accept each other. They communicate openly. There’s equality – someone isn’t the dominant friend while the other plays the submissive role. That’s not friendship; that’s an abusive relationship.

Friends back you to try new things. They want to see you become the best version of yourself. They introduce you to other people they think you’ll get on with. They’re there when things go wrong, not to say “I told you so,” but to help you figure out what’s next.

And friendships last. Not necessarily forever – sometimes we move away, interests change, life happens. But we don’t start friendships with an end date fixed from the outset.

Yet somehow, we’ve decided that funding relationships should work completely differently. Short-term. Transactional. Hierarchical. With detailed reporting requirements and predetermined outcomes.

At Raiser, we ask funders to commit to two years as an absolute minimum (though we’re considering raising that to five), ten years as a target, and twenty years plus? We’d hang the bunting, roll out the party food, and hire a balloon modeller.

It’s a beautiful thing when the friends you made at high school – while you were rough and ready, figuring out who you were meant to be – rock up to celebrate your 40th birthday party with you, by which time you’ve figured out what life’s about and are really making headway in the world.

Imagine if funders operated like this.

Instead of the current approach: “Here’s money for this specific project, deliver exactly what you promised, report back in 12 months, then we’ll probably fund someone else for a while.”

Try: “We believe in your mission and your people. Here’s sustained support to do your best work. When you want to try something new, talk to us. When something doesn’t work, let’s learn from it together. We’re introducing you to these other organisations because we think you’d make great partners.”

The security paradox

Short-term funding creates exactly the opposite of what funders say they want. When organisations never know if their funding will continue, they become risk-averse. They can’t invest in systems or staff development. They can’t plan strategically. They spend huge amounts of time and energy constantly chasing the next grant instead of focusing on impact.

It’s like trying to build a friendship where someone might ghost you at any moment. You’d never be fully yourself. You’d always be performing, trying to be what you think they want rather than who you actually are.

Long-term commitment creates the conditions for innovation, risk-taking, and genuine impact. When organisations know their core work is secure, they can experiment. They can fail fast and learn quickly. They can focus on the work instead of the next application.

What this looks like in practice

Having led a small charity myself, I know what this kind of funding would enable. Any charity leader reading this will recognise what I’m talking about.

With that security, we would:

- Take bigger risks because we wouldn’t be terrified of losing funding if something didn’t work perfectly

- Develop stronger leadership because we could invest in our people

- Create more sustainable impact because we could plan beyond the next funding cycle

- Build better partnerships because we wouldn’t be competing with everyone for the same short-term pots

Most importantly, we would be able to focus on the people we’re trying to help instead of constantly performing for funder

The courage to commit

Long-term funding requires courage from funders. It means backing your judgement about people and organisations. It means accepting that some investments won’t work out perfectly. It means giving up some control over exactly how your money gets spent.

But this is what friends do. They back each other’s judgement. They accept that not everything will go to plan. They trust each other to make good decisions.

The alternative – the current system of short-term, project-specific, heavily controlled funding – might feel safer, but it’s actually much riskier. It wastes enormous amounts of money on application processes and reporting. It prevents the kind of long-term thinking that creates sustainable change. It burns out great people who spend more time fundraising than doing the work they’re passionate about.

Let’s stop jumping from one funding relationship to another, never really committing to anything long-term.

The best change happens when great people have the security and trust to do their best work.

That requires funders who are willing to be friends, not just donors.

Ready to build lasting partnerships instead of transactional relationships?

If you’re a funder who wants to support long-term change instead of short-term projects, we’d love to talk about how Raiser can help you build genuine partnerships with the organisations you fund.

Learn more about partnership funding