The pattern is always the same. The Industrial Revolution promised an end to physical drudgery, but workers just found themselves in factories working longer hours than ever. In the early 20th century, when electricity transformed manufacturing, and productivity soared beyond anything previously imaginable, economists like John Maynard Keynes confidently predicted that by 2030, we’d be working just 15 hours a week. But instead of unprecedented leisure we invented computers, the internet, and smartphones – and now we’re never away from work.

Each promised technology eliminates some high-friction labour, and lots about that is good. Why, for example, would you now use a hand loom when a machine can weave fabric for you? But each time, new work emerges to fill the void. And crucially, it’s always the powerful who capture most of the benefits.

Now, in the early part of our own century, we have our own shiny new technology to grapple with: AI. Are we going to follow the same script?

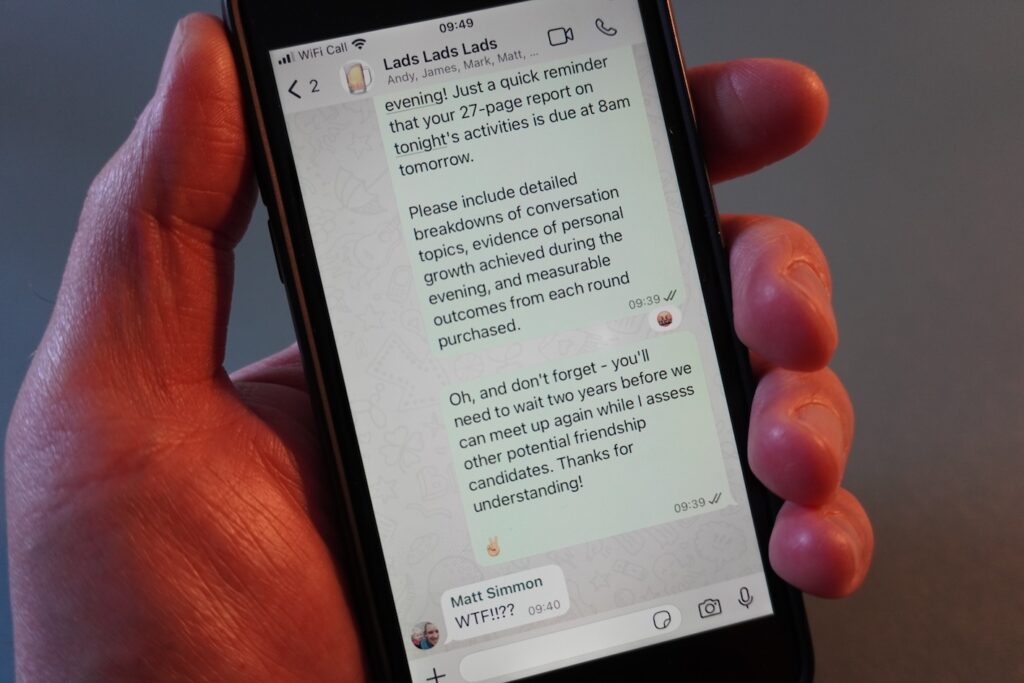

We’ve watched the fundraising sector’s AI journey unfold over the past year and a half. First it was “don’t use ChatGPT to write bids – it makes things up!” But then came the inevitable pivot: “Here’s how to prompt AI to write brilliant funding applications.”

Now funders are responding. Some are using AI to assess bids, others simply shutting their doors because they’re drowning in AI-generated applications.

But here’s what’s different about this technology: it doesn’t require massive capital investment or institutional ownership. Unlike electricity or early computers, large language models are democratised from day one – free tools, cheap paid versions, accessible to anyone with an internet connection. This changes everything. For the first time in history, the organisations closest to social problems have the same access to transformative technology as the institutions with all the money.

The problem is, we’ve AI-ed the wrong thing.

Making grant applications more efficient is missing the point. Funders get overwhelmed, and charities just spend their time serving algorithms instead of communities, as their bid-writers morph into prompt-engineers.

But what if charities stopped waiting for funders to fix the system and built their own solution instead?

Large language models work brilliantly with words – which means the stories of real change can finally carry as much weight as spreadsheets. Charities can now interrogate a mosaic of ‘fuzzy’ but meaningful data about the work they do and the impact they make. The person who says “you saved my life today” can be heard alongside the statistic that “300 people visited our food bank last week”.

This creates the possibility of flipping the entire dynamic. Instead of “please fund our project,” it becomes “here’s incredible change happening in the world – if you want your money to make an impact, then here’s how you can”.

Communities bring lived experience and solutions. Charities bring expertise and delivery. Funders bring resources. When technology enables everyone to tell their story powerfully, genuine partnership becomes possible.

The grant application is the hand loom of history – no good now for anything but firewood. Let’s use it to light a bonfire and celebrate a new era of mutual respect and effective, efficient change.

Luke Wilkinson is a fundraising consultant and former charity CEO, currently co-creating Raiser–an AI-powered tool for small charities–with James Poulter, a trustee of Christian Aid and ethical AI expert.

This article originally appeared in the September 2025 edition of Fundraising Magazine.